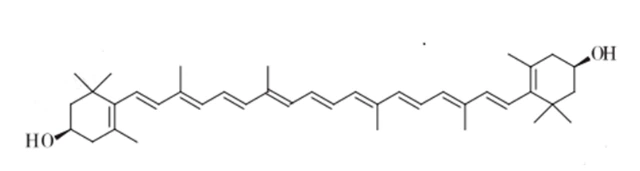

What is Zeaxanthin? Zeaxanthin, with the semi-systematic name 3,3′-dihydroxy-β-carotene, is a carotenoid characterized by its molecular formula C40H56O2. As an oxygen-containing pigment, zeaxanthin is non-polar and an isomer of lutein. Found in nature predominantly as the all-trans isomer, zeaxanthin showcases strong hydrophobicity and minimal solubility in water. In biological systems, it tends to reside in lipophilic regions, such as the cell membrane’s inner core, or forms complexes with proteins.

Physically, zeaxanthin appears as a blood-red oily liquid above 10 ℃, transforming into a yellow semi-solid oily substance below this temperature. It is odorless, exhibits excellent oxidation resistance, and withstands alkaline conditions. Zeaxanthin demonstrates stability under low-temperature conditions and outperforms other carotenoids when processed rapidly at high temperatures. While it is less stable to certain ions, it boasts remarkable stability against Fe3+ and Al3+. Light, especially in the visible and ultraviolet regions, significantly influences zeaxanthin’s stability, with the compound maintaining relative stability under standard temperature and natural light conditions.

Zeaxanthin cannot be synthesized within the human or animal body and must be obtained through dietary sources. Dark green vegetables, corn seeds, wolfberries, physalis fruits, and certain bacteria, including Cyanobacteria, Mycobacteria, Erwinia, and Flavobacteria, are primary natural sources of zeaxanthin.

In industrial extraction, marigold extract and corn gluten powder serve as ideal raw materials. Marigold, with its wide planting range and rich zeaxanthin content, is a prevalent choice for extraction. Corn gluten powder, a by-product of corn processing, contains zeaxanthin and lutein, making it a valuable alternative.

Foods with High Zeaxanthin: While the body initially contains a certain amount of zeaxanthin, it doesn’t regenerate over time. Therefore, dietary intake becomes crucial for maintaining optimal levels. Foods rich in zeaxanthin include spinach, kale, corn, pistachios, egg yolk, freekeh, orange peppers, broccoli, turnip greens, and various other green, leafy vegetables. Additionally, dietary supplements or vitamins can contribute to zeaxanthin intake.

Zeaxanthin Uses:

- Colorant: Zeaxanthin’s inability to convert into vitamin A makes it deposit in the body, imparting strong coloring abilities. It enhances the color of egg yolk and the flesh of fish and shrimp, elevating food quality and nutritional value. With a focus on natural pigments, zeaxanthin is approved by the European Union for its safety and natural attributes, positioning it as an ideal food colorant.

- Dietary Nutritional Supplements: FDA approval designates zeaxanthin as a new nutritional additive. Its inclusion in functional foods is on the rise, with studies indicating increased serum zeaxanthin levels through fortified eggs. Products like lutein + zeaxanthin capsules are developed to prevent tumors, enhance immunity, reduce cardiovascular diseases, and offer skin photoprotection.

Zeaxanthin Benefits:

- Protective Effect on Vision: Zeaxanthin, concentrated in the macular spot of the retina, plays a pivotal role in protecting against light-induced oxidative stress. Its affinity for ocular tissues and antioxidant properties make it indispensable for maintaining eye health and visual protection.

- Cancer Prevention: Zeaxanthin’s ability to inhibit cell lipid peroxidation sets the stage for cancer prevention. Studies indicate its efficacy surpassing that of β-carotene, with mechanisms tied to oxidative stress regulation, ATP production inhibition, and p53 mRNA up-regulation.

- Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease Prevention: Zeaxanthin and lutein, existing in complexes within animal cells, exhibit properties that reduce medial thickness in arteries, potentially preventing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

- Protective Effect on Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Response: Zeaxanthin’s impact on regulating pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors showcases its anti-inflammatory potential. In models of fatty liver, zeaxanthin dipalmitate demonstrates anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting specific signaling pathways.

In conclusion, zeaxanthin emerges not only as a critical component for eye health but also as a versatile natural compound with potential benefits across diverse health domains. Its stability, safety, and multifaceted advantages position it as an appealing candidate for various applications in the fields of food, medicine, and dietary supplements.